Illness experiences can oftentimes be difficult to put into words, as pain and suffering easily cross the boundaries of language. In The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, Bauby’s disability occasionally hides behind his storytelling. The audience temporarily forgets how he communicates his narrative by only blinking his left eye (Bauby 4). However, in the film adaptation, Bauby’s locked-in syndrome cannot be overlooked because it is prevalent in most scenes. Graphic memoir functions in a similar way, where images can be used to evoke meaning beyond language and depict concepts not easily placed into words. In My Degeneration, Dunlap-Shohl’s illustrations and visual techniques, such as spacing, are tools readers can use to more closely imagine how Parkinson’s Disease (PD) can impact an individual’s life.

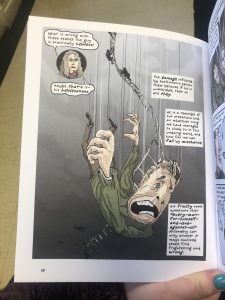

Dunlap-Shohl’s drawings provide context to his illness experience that would otherwise be lost in textual form. In Figure 1, Dunlap-Shohl describes becoming “smellblind” as a symptom of PD (51). The associated image of him preparing to step in dog feces provides just one implication of this condition. Although his facial expression makes the situation seem light-hearted, Dunlap-Shohl prompts us to explore how smellblindness impacts other areas of life, such as the inability to smell your favorite meal or experience memories triggered by olfactory sensations. If Dunlap-Shohl’s description of smellblindness had no supporting illustration, it would have been clumped in with the long list of PD symptoms and forgotten. However, the depiction contextualizes this phenomenon and hints at how PD can truly control even the smallest aspects of life.

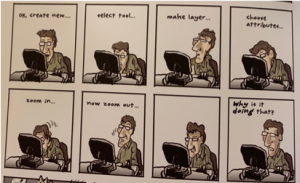

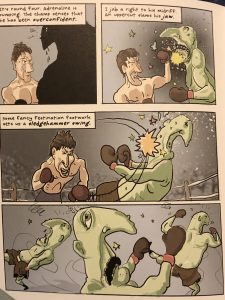

Spacing the panels in a particular fashion is another technique Dunlap-Shohl uses to evoke meaning. In Figure 2, Dunlap-Shohl depicts his task to learn photoshop in order to preserve his passion of graphic drawings as his disease progresses (41). This process is divided among multiple panels, which suggests his efforts were long and tedious. The space between the panels implies passing time, and it isn’t until later illustrations he expresses the temporality of the process through words. Simply stating the steps of building a photoshopped image, such as “create new, select tool, make layer…” shadows the meaning behind Dunlap-Shohl’s efforts (42). Mastering photoshop was important to Dunlap-Shohl because he knew PD would hinder his ability to draw, and his determination is conveyed in Figure 2 through illustrating the demands and accommodations Parkinson’s requires.

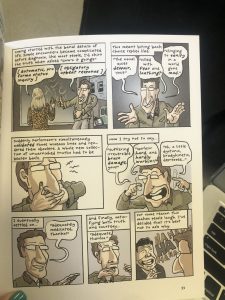

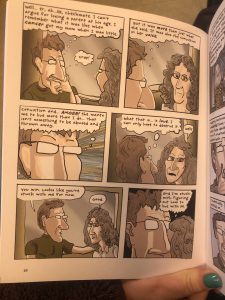

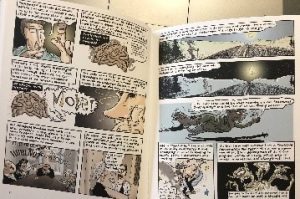

Dunlap-Shohl’s illustrations also allow for a more complete understanding of certain ideas he communicates. For example, in Figure 3, he describes how you cannot assume others are healthy simply because you are not (61). He depicts seemingly healthy people, but writes that they suffer from an illness of some sort that is not outwardly evident. Simply hearing the names of certain illnesses produces a stigmatized image of what that affliction looks like, but this image is not universal. Through pairing this idea with an illustration, Dunlap-Shohl limits the assumptions one can make about an illness experience.

Dunlap-Shohl, Peter. My Degeneration. University Park, The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2015.

Bauby, Jean-Dominique. The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. Paris, Editions Robert Laffont, 1997.

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. Directed by Julian Schnabel, performances by Mathieu Amalric, Anne Consigny, Emmanuelle Seigner, and others, Pathé Distribution and Miramax Films, 2007.

Paragraph 2. Image to the right.

Paragraph 2. Image to the right.