In the beginning of the semester, we focused a lot on Arthur Frank’s classification of narratives: the restitution, chaos, and quest narratives. Throughout previous classes, we have seen repetitive examples of this division of narratives, most of which fall into more than one category. However, when it came to the quest narrative, it seems to be more difficult to envision a narrative that is completely focused on the accepting the illness and being completely honest to the situation, besides Nancy Mair’s story. Yet, interestingly enough, Dunlap-Shohl, in his graphic memoir provides us with a thorough and holistic overview of what the quest novel should look like.

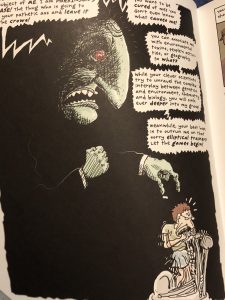

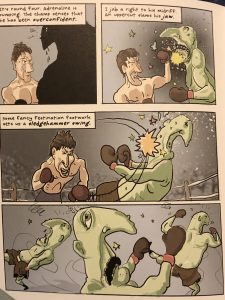

Throughout his graphic memoir, Dunlap-Shohl provides detailed images of his experience with Parkinson’s disease. His encounter appears to be what Frank would refer to as a quest narrative, mainly because he is gifted a voice to be the teller of his own story, a critical aspect of what the quest narrative is[1]. Yet rather than be a typical quest narrative that describes one’s illness, Dunlap-Shohl uses his own interpretation and skillsets to showcase his narrative through the use of images. The images offer the readers the opportunity to better understand Dunlap-Shohl’s views of his condition. For instance, Dunlap-Shohl creates a personified version of Parkinson’s and gives the disease its own character[2]. This decision allows the readers to insight as to what Parkinson’s means to Dunlap-Shohl and the way he views the disease. Moreover, by the end of the story, we see that the same image of Parkinson’s is used again. However, rather than in a form to intimidate, the manifested image symbolizes Dunlap-Shohl’s growth in acceptance of the disease and his willingness to fight back. This switch in mentality corresponds with Frank’s belief that in the quest narrative, the ill person surrenders control of health yield, which is precisely what Dunlap-Shohl does.

One major action that differs from Frank’s description of the quest narrative is Dunlap-Shohl’s use of the word memoir. In Frank’s definition, he recalls that a memoir is very gentle and is told stoically without any “special insight”. And while this may hold true to some aspects of Dunlap-Shohl’s graphic memoir, like how he chooses to not linger on the moments of anger, it is not the complete truth. Rather, Dunlap-Shohl offers a memoir that is not entirely stoic. He mentions his battling thoughts with suicide, his annoyance with the disease as it tears at his ability to work, and even the tears shed between him and his wife among hearing about his diagnosis. This is not to say that Frank is wrong in his definition of a memoir, however, it does serve to act as an alternative opinion on the appearance of a quest narrative in a differing form of memoir.

[1] “The Quest Narrative,” 75-136.Frank wounded storyteller ch 6

[2] Dunlap-Shohl, Peter. My Degeneration: A Journey Through Parkinson’s. Pennsylvania State University Press, 2015.