Before the book even begins the reader is presented the table of contents: here lies the road map of the graphic memoir that equips the reader with what to expect in the pages to come. The organized list of titles is contrasted by the sporadic background of what appears to be snow. Upon a closer examination we can see circles and even letters. The author can be found in the corner: cold and alone. The difference between the uniform types words and the hand drawn letter and circles can show how the unpredictability PD and the comfort of Dunlap-Shohl’s career are combined into one page. The letters and circles seem to be hand drawn, perhaps the author was practicing his letters as his condition progressed. The black border at the top of the page is almost like a transition of what our reality and narrative is to the author’s story. it is like Without getting into too much of the contents of the graphic memoir, one is able to graph the type of narrative Dunlap-Shohl is presenting.

The first title explicitly tells us that there is a sad beginning, the author is going to experience his diagnosis of Parkinson’s and is experiencing depressing feelings. From the second title, the reader can infer that he is learning to understand and work around the struggles of having PD. There is an educational experience that comes with an illness that changes one’s life. It is like a culture with its own language and mannerisms and one must adapt to it because it takes on a visible role in one’s life.

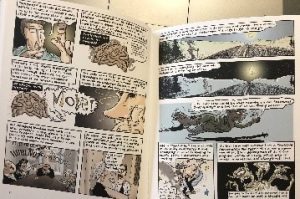

In the third chapter, Parkinson’s is personified to create an identity for the disease: separate from the author. Though they are of the same body, they are two different “people”. This can be interpreted as the author not accepting PD as a part of his life and as a part of himself while also understanding that he is still a multifaceted person though he has a debilitating disease.

The fifth chapter’s title along with the chapter’s first page shows a confusing reality. This notion is supported by the graphic novel-esque form: cartoons and drawings are not reality. They mimic reality but are not a complete copy of what is perceived as 3D or real. The prism is not only changing his view on life but also how the author is viewed by others: “it changes the way you perceive things and the way you are perceived” (Dunlap-Shohl 50). It is a combination of the disease, medication, and his personal thought processes that create his reality.

The last chapter title reminds me of a musical where musical numbers have reprises, or songs that appeared earlier and entering the story once more. Reprise means to repeat, to show up again: which is odd to think that there is another diagnosis for a disease that does not “leave” or have the ability to “come back”. Yet the last title has a more hopeful meaning in a sense that the author is returning to where he started. There is a tone of finality: a final negotiation of the diagnosis and its meaning for the author’s life.

A restitution narrative does not seem fitting due to the nature of Parkinson’s, there is no return to a life without Parkinson’s once one is diagnosed: “Yesterday I was healthy, today I’m sick, but tomorrow I’ll be healthy again” (Frank 77). They are restored to their former self, pre-illness with the help of medicine. I don’t think any story about Parkinson’s will fit the restitution narrative. “So mark this moment with gratitude and relief, and anticipate the next ten years” (Dunlap-Shohl 96). This quote contradicts the end of what a restitution narrative should end like, it is ten more years of living with Parkinson’s disease.

The titles are giving the reader a timeline which contradicts the chaos narrative which is anti-narrative in a sense. Chaos narratives “are chaotic in their absence of narrative order” (Frank 97). The progression of Parkinson’s is “linear” for everyone though there is a lack of control because there is no cure for Parkinson’s. Events are not by chance, they are predictable in the sense that the patient will progressively get worse and lose their motor skills. There is a sequence of events that Peter Dunlap-Shohl is telling the reader: there is a beginning, middle, and end.

From the titles, there does seem to be a journey that is compliant with a quest narrative. “Quest stories have at least three facets: memoir, manifesto, and automythology” (Frank 119). There is a plot, the genre is a graphic memoir, and there is a story acceptance.

Dunlap-Shohl, Peter. My Degeneration. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2015.

Frank, Arthur W. The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics. University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Paragraph 2. Image to the right.

Paragraph 2. Image to the right.