As someone who has been following the news on the Covid-19 pandemic diligently since February, I didn’t find out anything new from the Vox article. I thought Eliza Barclay successfully combined many sources and clearly laid out the importance of social distancing – if I had to choose one article to show to someone who does not pay attention to the coronavirus situation, this might as well be the one. I very much enjoyed the Flatten the Curve GIF by Dr Siouxsie Wiles – this is a very important graphic that she made extremely clear and fun with the design. I had a look at her Twitter account and saw another great graphic she made about masks. (https://thespinoff.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Covid-19-Masks-05.gif). The GIF shows what types of masks should be used and how to use them safely. CDC now recommends that everyone wears a cloth face covering (such as a home-made face mask) in public settings. I’ve been finding it quite frustrating that the information about wearing face masks has been confusing – with different countries and doctors recommending different things. Many governments, including the US, were reluctant to advise people to wear them – which I can understand as there simply would not be enough left for those at the greatest risk of infection, healthcare workers in particular. Though cloth and surgical masks are not as effective as N95, they can play a role in reducing the spread of covid-19 – if used properly. Unfortunately, I’ve seen so many people wearing masks and touching the outside or adjusting them constantly – as I travelled home a few weeks ago, the number of people who were ineffectively using face masks at the airport without knowing it astonished me. It also worried me when I heard some of my friends say there’s no need to wear a face mask on the plane as they heard that they don’t really help– which is simply not true. While stock-piling masks is definitely not something we should be doing, wearing a mask we already have or making one and re-using it after cleaning is definitely a good idea, especially in in public spaces. The advice saying “masks are useless in stopping covid spread” unfortunately has led to a lot of disinformation. It is very important to educate the public on how to make our own & properly use masks – this way we can protect essential workers when we go to the supermarket. I find it very disheartening that the US president, despite being in contact with many people on a daily basis, refuses to wear a face mask and many other leaders, including Boris Johnson, were unable to set an example by practicing physical distancing and safety measures. Though I’ve written this post mostly about face masks, those who can should practise physical distancing as this has been proven to be most successful measure to slow the spread. I choose to call it physical distancing, as I’ve heard (and agreed) that the phrasing “social distancing” implies to many people that they cannot socially interact and be with others. Of course, we cannot physically be with them, but socially we can interact – on social media or by calling each other daily. The choice of words in this case may make some people less likely to stay in their homes as “social distancing” sounds scarier & is not really accurate in what it means.

Author: aleks474

My Degeneration reading response (4)

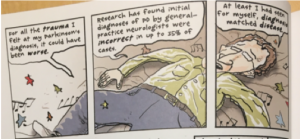

There is a light-heartedness in using the medium of a graphic novel. In Peter Dunlap-Shohl’s My Degeneration, comics open the door for more people to engage with and understand the experience of Parkinson’s disease. Because of the stigma present in our society, long-term illness is not spoken about often – in My Degeneration, things that would be potentially awkward or embarrassing to talk about are laid out in a visually engaging and accessible way. Dunlap-Shohl uses images and words to convey movements, emotions, sounds to create a humorous and personal memoir which made me understand and deeply appreciate the graphic novel.

In the two frames on top of the page on the left (p.69) Dunlap-Shohl represents his body and its movement in relation to other people, “the non-Parkinson world”. On the left, he is the only sharp, coloured-in figure while the other people are blurry, suggesting movement. He is frozen in time. Alternatively, his medication causes rapid movements and convulsions: on the right, he is the arms of his body drawn repeatedly, the image of his body blurry, distorted. The real world is drawn in two frames, while the drawing of the underwater world beneath has no borders – a world inside his head. The overall image suggests Dunlap-Shohl feels like he is falling from the “normal” world into the deep waters of Parkinson’s and depression. “Unemployed”, “angry”, “anxious”, “frustrated”- the words describing him he draws in clouds – like spots on his consciousness.

In the two frames on top of the page on the left (p.69) Dunlap-Shohl represents his body and its movement in relation to other people, “the non-Parkinson world”. On the left, he is the only sharp, coloured-in figure while the other people are blurry, suggesting movement. He is frozen in time. Alternatively, his medication causes rapid movements and convulsions: on the right, he is the arms of his body drawn repeatedly, the image of his body blurry, distorted. The real world is drawn in two frames, while the drawing of the underwater world beneath has no borders – a world inside his head. The overall image suggests Dunlap-Shohl feels like he is falling from the “normal” world into the deep waters of Parkinson’s and depression. “Unemployed”, “angry”, “anxious”, “frustrated”- the words describing him he draws in clouds – like spots on his consciousness.

In Image 2 (p.77), the lack of borders around the image again suggests that we are in Dunlap-Shohl’s mind. The drawing depicts his perception of the post-surgery events: windows in the darkness reveal the distorted image of the doctor, rendered by his brain while recovering from anaesthesia. The text is the commentary within the brain of Dunlap-Shohl. Not communicating with the doctors, he is stuck in the dark frame and simply looking out of the windows. He is lacking freedom and control over his body during the procedure which is supposed to give him exactly that.

In Image 2 (p.77), the lack of borders around the image again suggests that we are in Dunlap-Shohl’s mind. The drawing depicts his perception of the post-surgery events: windows in the darkness reveal the distorted image of the doctor, rendered by his brain while recovering from anaesthesia. The text is the commentary within the brain of Dunlap-Shohl. Not communicating with the doctors, he is stuck in the dark frame and simply looking out of the windows. He is lacking freedom and control over his body during the procedure which is supposed to give him exactly that.

Spaces between frames in a comic imply a change of location or time: as a reader we understand that something happens between them. I found the image on the left (p.8) particularly interesting because of the use of frames, which Dunlap-Shohl uses to fragment his body. On the page before, he is crushed by a falling piano, a representation of the feeling of finding out about the diagnosis. In this image, frames of the comic disconnect his limbs from each other: space and time comes between them. Conveying the feeling of confusion and fragmentation upon hearing the news, the image also predicts the changes his body will go through due to Parkinson’s: him limbs not responding in the way he wants them to, leaving him feeling disconnected from himself.

Source of images:

Dunlap-Shohl, Peter. My Degeneration. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2015.

Reading Response to Berger’s A Fortunate Man

“One of them shouted a warning, but it was too late.” (p.17)

With the very first sentence of his story, Berger throws his reader right into the unknown: there is no setup, introduction of the place or characters. This short piece is an example of ethnographic writing, a social observation which Berger wrote while accompanying an English country doctor. The writing is fast-paced, mirroring the action of the doctor hurrying to save the man crushed by the tree. The narrator of the story is Berger himself: an observer, not emotionally involved in the events but reporting on them. His writing, however, is not devoid of emotion: behind the events, Berger conveys emotions which paint an image of his characters: pain of the injured man, worry of the onlookers and dedication of the doctor.

The doctor is the main focus of Berger’s writing: he is the one whose actions we follow from the moment he gets the call about the accident until the injured man is taken away in an ambulance. Conveying the reality of the country doctor’s life is at the heart of the story. As people around comment on what’s happening, the doctor’s attention is focused on helping the trapped man. He also takes the time to explain what he’s doing to the three onlookers, reassuring them. Berger wonderfully captures the reactions of the onlookers to the doctor’s presence and his actions. To them, he is a friendly saviour but also a not-always-welcome outsider. To the injured man, he is a source of courage and hope.

“The three onlookers were relieved by the doctor’s presence. But now his very sureness made it seem to them that he was part of the accident: almost an accomplice” (p.18)

“Again the doctor, whom they knew so well, seemed the accomplice of disaster” (p.19)

So strongly tied to ideas and memories of illness, the country doctor seems to the people a part of the accident. His presence is synonymous with the presence of illness and injury. At the same time, he can relieve pain and illness but also be a constant reminder of their existence. The above sentences convey the mixed emotions people have towards doctors and reveal a truth about being one. The country doctor is a friend who is only present during most difficult and unpleasant of times. When that time is over, he doesn’t necessarily want to be remembered.

Works cited:

Berger, John, and Jean Mohr. A Fortunate Man: The Story of a Country Doctor. Canongate, 2016, pp. 17-19